How I Learned to Write the Hard Stuff

I wanted to write about my traumatic personal experiences, but I was hiding behind walls. This is the moment when I finally broke through and found my voice.

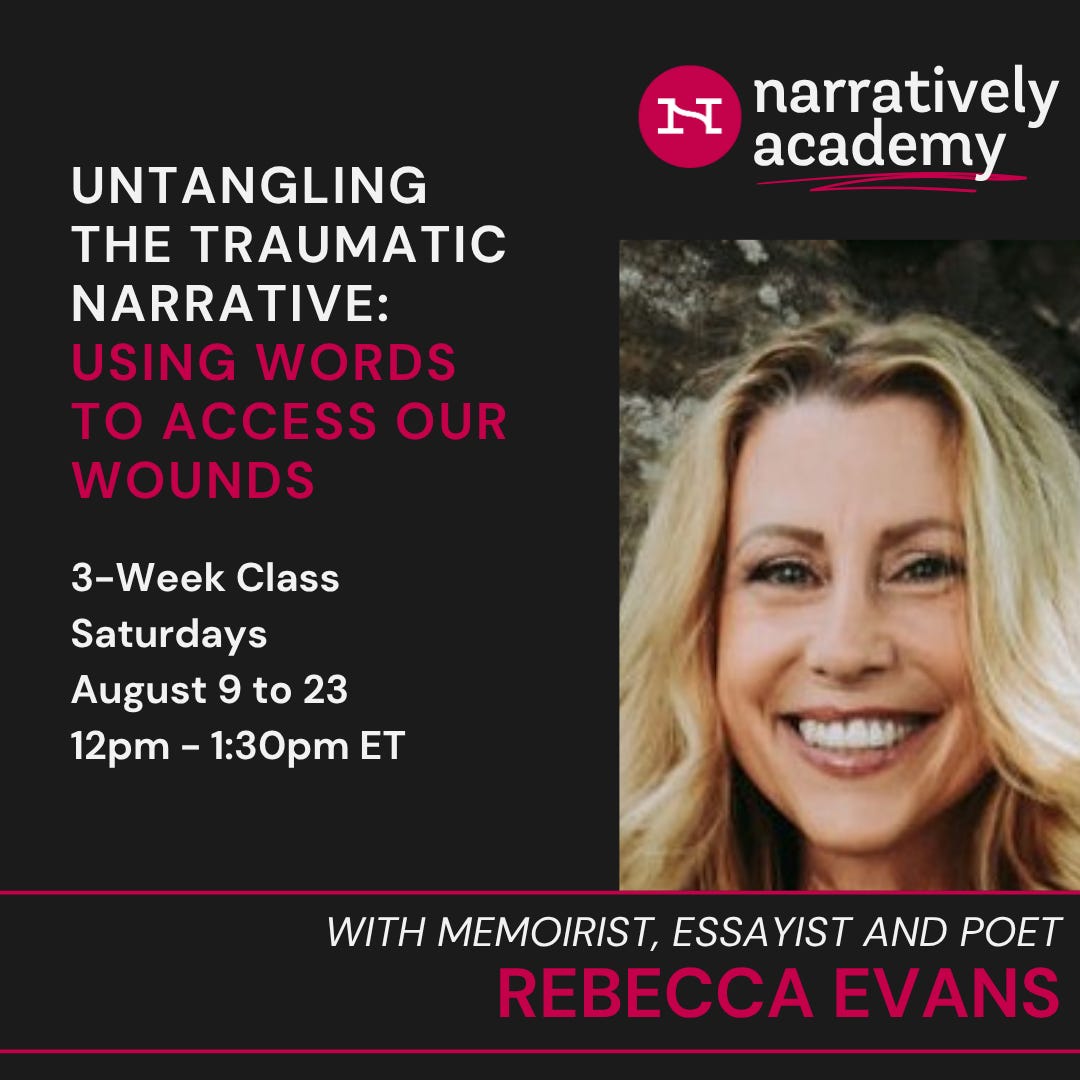

In our upcoming three-part workshop Untangling the Traumatic Narrative: Using Words to Access Our Wounds, Rebecca Evans will share from her own extensive experience confronting the fear and vulnerability that surfaces while untangling difficult narratives on the page. Today, we asked Rebecca to share this story about how she first got to the place where she was able to start writing about her most traumatic life experiences.

I wrote nonfiction in third person. It’s a strange method to approach narrative, essay and memoir. An unusual way to share a personal story. Most of my work had read like fiction and often, held a gap between the main character (me) and the audience. I told myself that this POV worked, writing my narrative from a “she” instead of a “me” perspective.

In writing groups and workshops, my short essays were processed as if fabricated. Feedback proved difficult, especially when a writer stated, “She would never do that” or, “I don’t believe this happened.” Reminders that I’d not established enough of my protagonist (me) on the page. Even better advice consisted of, “You might think about her doing this instead…” followed with ideas on how my character, meaning me, should behave. It felt like a blend between lecturing and counseling. Yes. I wish more of my interior (me) appeared on the page. Yes. I wish my character (me) had behaved differently. Don’t we all?

Yet my form with third-person memoir had succeeded.

I found, through the use of third person, I could write the hard stuff, the stuff that damaged me, that changed me, that shamed me. I could write as if I were writing about somebody else. As if this narrative had little to do with my own experiences. In this approach, I found myself raw, real and willing to commit to truth. I also discovered that I edited less when writing prose more loosely attached to me. Hence the need for “she.”

In 2018, during my first residency at Sierra Nevada’s M.F.A. program, I braced myself to read at the open mic. I’d drafted a few excerpts from a larger manuscript stowed in a file, awaiting revision. The section I selected was born from the writing prompt, “If These Old Walls Could Talk.” At the time, I trained in poetic therapy and this prompt was often used in group settings.

The essay developed and, as usual, carried a distant third-person POV. I further distanced the narrator, offering perspective through my childhood walls. Before the reading, I talked to my mentor, Suzanne Roberts, and she gently asked why I chose third person, why I chose walls.

“This keeps you safe,” she said, “distant from, not only your own story, but from the reader. Your material might be too hard to do this, but maybe try to tell it in first person.”

She pointed out that if I stayed behind the walls, secure but hidden, I created even more space between my own story and me. Between my reader and me.

The revision of this one-page excerpt brought me to my barren floor that night, alone in a dorm room in late summer Nevada. I had broken other barriers in my writing the first few days in the program, connecting with other writers, searching for my identity as a woman, as a writer. I watched a mamma bear and her two cubs, less than 20 feet from my study group, softly step across campus in the hazy gray sky, reminding me that protection of one’s children need not be brutal or violent, but could simply live as a presence. Reminding me that writing, even with a group of passionate, creative spirits and Mother Nature herself, was ultimately a solo flight. Reminding me that my interpretation of that bear carried a unique lens, that the way I capture my story will be through, not just my eyes and my memories, but my heart.

I needed to connect my story to me. I needed to own my story.

My voice cracked, alone in my room, trying to read that single page in first person, aloud to my reflection. I couldn’t. Saying “me” and “I” aloud felt like a stone in my throat. How would I read this in front of a room of writers, many successful published authors? I told myself, if I could read, I could do anything.

I don’t mind the microphone. I’m a public speaker, a motivational coach, a television show host. I was Mrs. Idaho in 2004. I usually accept attention. When it was my turn to speak, I felt unstable standing at the podium. My hands shook and my voice sounded like someone else’s. I cried. I cried for my own story that I finally felt. One I hadn’t allowed into my heart or out and into the world. I cried for me and for my adopted sister and for any woman or child who has ever been abused.

For the first time, my story mattered. And now, every time, I read my words aloud after I write, whether in my journal, on scraps or a final revision. Giving my story my voice changed me. Breaking down my walls of silence offered purpose in my writing.

And this is why I write.

This is why we write.

Ready to find your voice? The author of this post, memoirist, essayist and poet Rebecca Evans, is leading Untangling the Traumatic Narrative: Using Words to Access Our Wounds at Narratively Academy, starting August 9. Students will explore how to write about difficult experiences—while taking excellent care of yourself.

This story was originally published in Fiction Southeast.