How to Mine Your Nonfiction for Novel Ideas

Sometimes flipping the perspective on your personal essays and articles—and seeing things from someone else's point of view—can lead to inspiration for fiction.

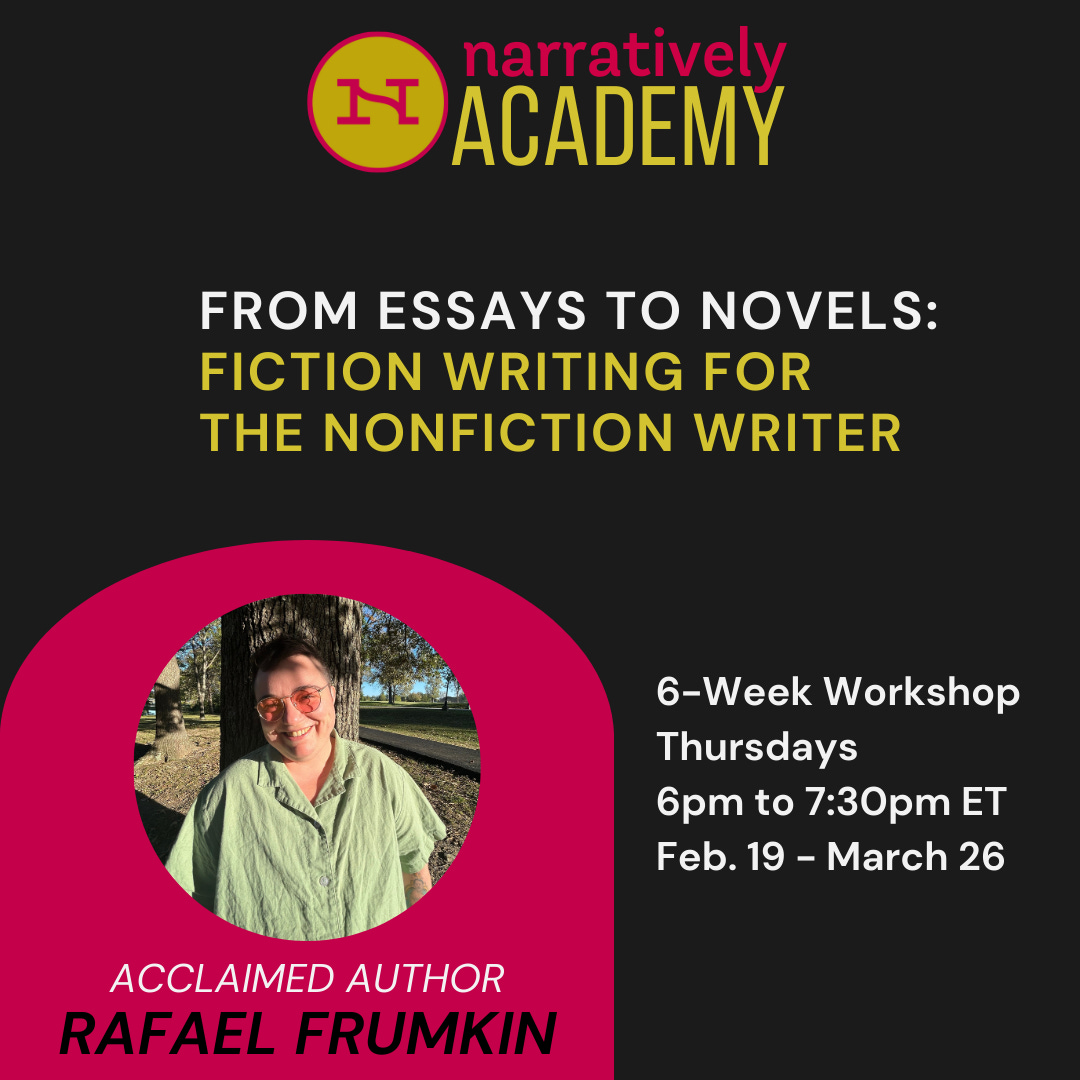

Later this month at Narratively Academy, Rafael Frumkin will teach a 6-week workshop, From Essays to Novels: Fiction Writing for the Nonfiction Writer. For today’s StoryCraft post, we asked Rafael to share a little about how essay writers can find leads for their fiction.

One major function of nonfiction is reporting on the truth. A report may look different depending on the nature of the reportage, because different people have different perspectives on real-life events. Are you adhering to un-skewed facts at whatever cost? Are you exploring your own subjectivity, or someone else’s? Are you testing the limits of memory?

Odds are if you’re reading this, you already know a thing or two about the impossibility of capturing the unvarnished truth. Regardless of your intent as a journalist, scholar or essayist, there’s no disowning the singularity of your viewpoint or the life that’s shaped it.

As someone who writes both fiction and nonfiction, it’s actually exciting to me that the truth can be such a tricky thing to pin down. It doesn’t mean that we’re awash in a sea of uncertainty, ungrounded by anything remotely resembling facts. What it actually means is that capturing the truth works more like writing a novel than churning out a quick-turn news dispatch: Each of us has our own impression of what’s happened and why, and those impressions play a far greater role in what happens next than we’re often willing to admit.

Acknowledging this is the first step toward mining your nonfiction for novel ideas. Embrace protagonist syndrome, even if it’s just as a thought experiment. Take a first-person piece you wrote, and consider the fact that while it’s one hundred percent nonfiction, it’s also one hundred percent your own perspective.

Ask yourself: How might X or Y event in my life have looked from a secondary or tertiary character’s perspective? How have you shaped the world around you to “fit” you? What does a world that “fits” look like versus one that doesn’t?

Please keep in mind that acknowledging the reality of your perspective isn’t the same as arguing that it’s the only one worth listening to. In fact, it’s quite the opposite: by reflecting on the fact that you may not be the sole arbiter of truth (or moral rectitude, or rationality, etc.) in a given situation, you are actually making space for other perspectives, and for the bigger truth—which is that reality is so much more complex than we want to believe it to be.

Go back to your essays and articles and memoir. Look them over for signs of where your perspective could end and others’ could begin. Write into that other perspective —no matter how scary or alien or taboo it feels—and see what comes of it. Train your gaze on yourself, but from a different set of eyes.

I’ve been doing a lot of thinking along these lines lately, and it’s resulted in the following exercise:

Consider a moment when a friend or family member with whom you’d been close said or did something that made you feel misaligned with and alienated from them. You know how you felt—confusion, fear, betrayal—so now write a monologue investigating their perspective. What sorts of circumstances, thoughts and emotions would conspire to cause someone to do this thing? You know how you perceived this person’s actions—but how might they have perceived yours? Once you’ve found your way into this new perspective, you might begin exploring other perspectives closer to it, or closer to but still distinct from your own.

If you’re feeling up to it, train your gaze on yourself training your gaze on yourself (hello, literary modernism!) You’ll no doubt be surprised what yields from that psychedelic hall of mirrors. Before you know it, you may well write the first chapter of your novel.

Ready to dive into fiction? In From Essays to Novels: Fiction Writing for the Nonfiction Writer, Rafael will help you put the considerable research and storytelling skills you’ve built as a memoirist, essayist journalist or scholar to work on your first substantial piece of fiction.