How to Listen to Your Story and Let It Tell You What It Wants to Be

I often find the key is to stop focusing on what I think the story should be and let the story guide me.

Good morning, writers! If you’re looking to jumpstart your creativity this Wednesday, Writers’ Room is on at both 8am ET and 8am PT today. Later today, at 1pm ET, is our live chat with author Ethelene Whitmire about how she turned her nonfiction article into a book.

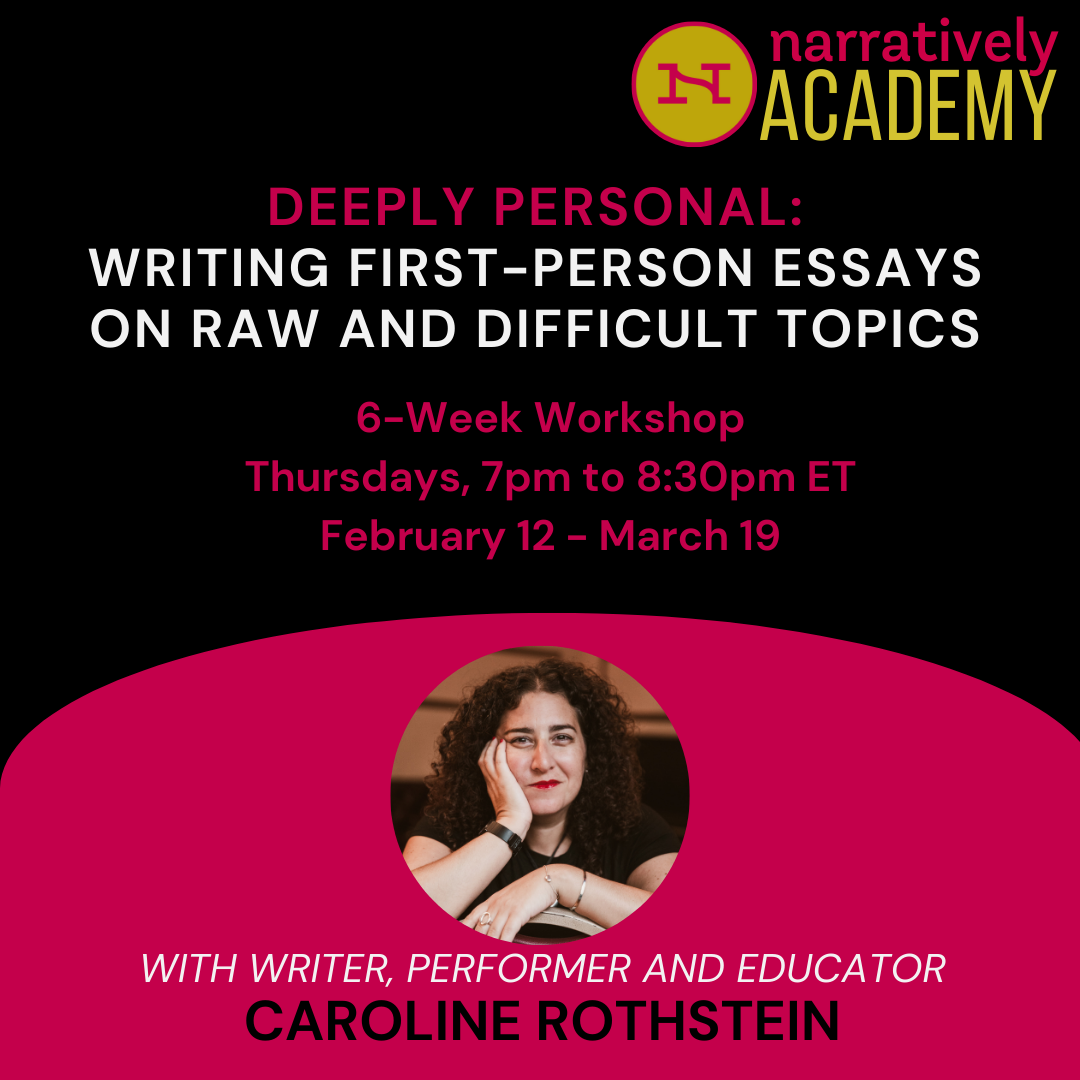

And just around the corner, starting February 12, is the next session of Caroline Rothstein’s popular class Deeply Personal: Writing First-Person Essays on Raw and Difficult Topics. Today, we asked Caroline to share this StoryCraft article about her own writing process.

My writing talks to me. It tells me who it is. Shows me––draft after draft after draft. And my job, as the writer, is not only to transmit and transmute the content that begs to pour itself out of my fingers as they dance across the home row keys, but to listen. To witness my piece—be it an essay, a poem, a stretch of dialogue for a novel or film, the nut graf of a reported feature, or the closing monologue of a musical or play—tell me who it is.

Let’s take my recent personal essay “Dust,” which appeared in “my word(s),” the quarterly nonfiction series I publish on my website. The essay inspiration came while watching A Cowboy Christmas Romance on Netflix (I’m a rom com film and romance novel fiend). Near the end of the film, there was a dust storm underway (soon to be treacherous with thunder and lightning and rain) to which I had a visceral reaction. Suddenly, it reminded me of a dust storm I drove through in 2007 while on a three-month solo road trip around the United States.

Now. Sometimes I write personal essays based on a topic I’ve been asked to write about. Sometimes it’s a topic I’ve wanted to write about, and suddenly something clicks and I’m able to let it pour and flow. And sometimes the piece finds me. Something out of nowhere—like lightning itself—strikes my inspiration, and I write. That’s what happened here. The latter. The piece took the wheel—pun intended; said: drive.

Here are the first four paragraphs of the first draft:

I was watching A Cowboy Christmas Romance on Netflix this past weekend on January 3, 2026, when, with exactly 18 minutes left to go in the film, a dust storm began to rattle the cattle ranch where the plotline took place. Suddenly, I was 23 years old on a three-month solo road trip around the United States of America, trucking my silver Volvo sedan I called “Antelope” (after the Phish song “Run Like an Antelope”) across Arizona in the wake of a wild dust storm.

My car felt mauled that day. I had just left the Painted Desert, a spectacular site featuring nature’s ability to turn itself into awe. Again and again. Nature’s built like that. Scientifically. Spiritually. Able to balance the forever both/and that is divinity and practicality.

I wish we did that more often. Us. Humans. That particular kind of balancing act.

We’re able to. Us. Humans.

After writing this opening, I really got in my own feelings about that road trip. I took the wheel back from the essay and went digging in my computer for an unwieldy 451-word paragraph I remembered writing in a book proposal for the book about this road trip I’ve been working on for 18 years (!!!). I copy/pasted the massive paragraph and plopped it in to now draft two of my “Dust” essay. I was sure this paragraph was a perfect fit.

Then I thought more about dust. I thought about poet Anis Mojgani’s “Shake the Dust,” which led me to bring some of the sentiments of Mojgani’s piece—about literally shaking the dust when stuff gets challenging and hard—into my essay. Now we were getting somewhere. The essay was telling me: This is who I want to be. Cool.

I wrote the rest of the piece. But when I got to draft five, something about that 451-word paragraph kept staring me in the face. I kept checking in with myself and my essay to ask: Do you (the paragraph) really want to be in this essay? Or am I (me, the writer) trying to force it based on my own nostalgia?

This is a thing I do. Maybe you do it too. I get super, duper wildly nostalgic in my personal essay writing and love including stuff that literally only matters to me. Like, little cute moments of connection or memories or moments that hype up my heart but have absolutely nothing to do with the writing content and task at hand!

I realized, as I got to draft 5, that’s what was going on with that 451-word paragraph. And only because I’m trying to prove a point here, in hopes of helping you learn to listen to your own work—and understand the difference between listening to our pieces and screaming over the voice of the piece itself (as I did with this massive paragraph)—I’m going to share it with you so you can see it—in comparison with the final published piece—and see why it doesn’t work:

It was on this same journey that I set the foundation for my adulthood. While stir-frying tofu and vegetables in Atlanta, where I spent six months working at a friend’s sports bar to save up for my road trip, I realized that, now financially independent for the first time in my life, I literally couldn’t afford to have an eating disorder, a realization that helped to feed and sustain my recovery. At the base of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, overlooking an abandoned construction site, it hit me that the civil rights movement was still very much underway, with all too little actual progress made, and that I would commit my life to helping see racial justice to fruition. At a Best Western in Clarksdale, Mississippi, I felt my hunger as a writer literally busting my bra from its seams as I stormed into my hotel room, tossed off said bra, and sat down at my laptop computer to write. In Santa Fe, New Mexico, I felt the mountains suck me in. They whispered into my ears. You’re an artist, they said. You’re on the right path, they kissed. There, I walked into a museum to find Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road” manuscript on display. Coincidentally. And I knew this was my road trip. Minus the drugs. Minus the misogyny. And so by the time I reached Canyonlands National Park in Utah, sitting alone at the mountain’s edge overlooking the Colorado River, I felt whole. I sat there with my legs crossed, my hair shoved into a tight, yet messy bun on top of my head, wisps jetted out behind the thick black cotton headband I would ultimately wear to its deterioration, my dead brother’s black Northface fleece engulfing my torso, my Oakley sunglasses adorning my skull, my ear holes filled with miniature silver hoops—two on the right, three on the left—my nose, mildly freckled by the sun scorched days I’d spent traversing ancient canyons in Moab, Utah. And I sat there thinking: this is freedom. This is the loneliness that encapsulates humanity. This is the infinity that G-d asks—begs, pleads, ushers—us to embrace daily. I sat there thinking, here I am alone at the edge of a cliff in Utah, and I have no one with whom to share this stunning glory, except for myself. I am the only person that will ever remember this moment I’m having. I can retell it for years and decades to come, but no one—no partner, no family member, no loved one, living or dead—can ever know what it was like at this moment on this day to sit in my flesh and taste this infinity.

It’s cute, right/write? Filled with feels. But it has nothing to do with the dust!

Each piece is unique. Each piece has its own voice. My job as the writer is to bear witness to the chorus of sounds driving the words (I’ve really mixed my metaphors here) and let them breathe.

Maybe your chorus looks—and feels—different. But I do feel strongly that, universally, each piece has its own voice. And learning to listen to it, especially with personal essays, where our own voices can often get in the way, is critical to letting a piece become its true, authentic and honest self.

We’ll be playing with things like this in my next cohort of “Deeply Personal: Writing First-Person Essays on Raw and Difficult Topics.” I hope you can join. Bring your voices. All of them. We’ll make a chorus of our own together in class.

Love this. Thanks so much for sharing.

Thanks for sharing your writing experience, Caroline. Reminds me of when a writing teacher I had said,

“Sometimes you have to toss out your baby.” We all have times when we take off in a riff and eventually discover as much as we like that bit, it just doesn’t work in the piece. It’s hard to do, but always a good idea. 😀